Imagining a Post-Coal Appalachia

Alana Semuels/The Atlantic

Alana Semuels/The Atlantic

WHITESBURG, Ky.—For a long time, coal dominated this remote region of rolling hilltops and muddy roads near the Tennessee and Virginia borders. But when the nation started to move away from coal-fired power plants, and giant companies pulled up stakes and closed down mines, shedding 7,000 jobs in just three years, the people left too. Some went to western Kentucky for mining jobs there, others headed to Lexington or Louisville. Nearly every county in eastern Kentucky lost jobs between 2000 and 2010.

Even before the mines started closing, children who grew up in Appalachia were often told to get out if they wanted to succeed. One-third of the regionlives in poverty. In one eastern Kentucky county in 2009, government benefits accounted formore than halfof the county’s personal income.

More From

- Can Business School Save a Company?

- Why Is It So Hard to Find Jobs for Disabled Workers?

- What Education Can and Can't Do for Inequality

“For people who grow up here or have roots in this place, parents and grandparents who know there’s not a lot of opportunity here encourage their loved ones to go and find jobs elsewhere,” Ada Smith, who grew up in this town of 2,000, the seat of Letcher County, told me. “It’s not that anybody hates this place, it’s just that they don’t want to see their family suffer.”

But in the last few years, in places across eastern Kentucky and especially in Whitesburg, young people have started returning. A record store co-op recently opened in town and holds events with musicians. A new tattoo parlor—started by a local man who returned from living in Louisville—draws people from across state lines and even other countries. When the city voted to allow restaurants to serve alcohol in 2007, two new bars opened. Three years ago, voters decided to let stores sell alcohol too. Last fall, the city councilnarrowly approveda permit for a moonshine distillery that's going to open in a historical building in Whitesburg's downtown.

Other recent additions include a cupcake store and a vape shop. But perhaps more important than the brick-and-mortar businesses is the sense among locals that there’s a growing commitment to staying in Appalachia.

“I knew I wanted to be in Whitesburg,” John Haywood, who owns the tattoo parlor, told me in his colorful basement shop decorated with his own artwork on the walls, which he opened four years ago. “There was what was to me a real grassroots movement here, still very early in its infancy, of just a lot of individual people trying to make stuff happen.”

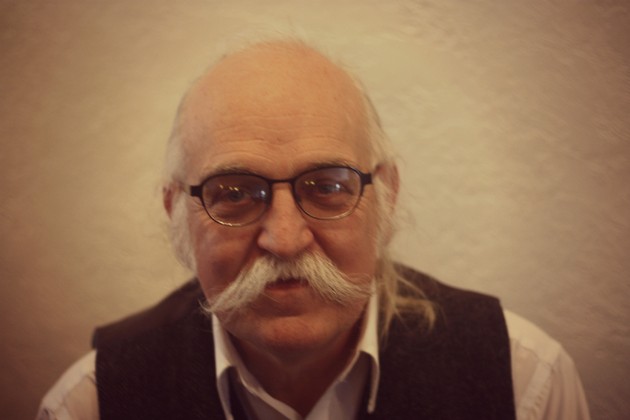

John Haywood in his tattoo shop (Alana Semuels)

John Haywood in his tattoo shop (Alana Semuels)

Whitesburg is unique in that it has a history of arts and culture bolstered during the 1960s. In that way, it is perhaps better poised to make a comeback than other regions of eastern Kentucky, including Owsley County, often mentioned as thepoorest countyin America. One-quarter of the residents in Letcher County, where Whitesburg is located, live below the poverty line, as opposed to 38 percent of Owsley County residents.

Still, dozens of regions across the country have struggled through the loss of major industries such as mining or manufacturing. Few were as poor as Appalachia when the decline began. If Letcher County can find a way to not only survive the decline of coal, but thrive despite it, other regions in Kentucky and in the nation may be able to as well.

* * *

There are many explanations for eastern Kentucky's poverty.

Perhaps the most famous account comes fromHarry Caudill, an outspoken lawyer from Whitesburg who served in the Kentucky House of Representatives and then became a professor of Appalachian Studies at the University of Kentucky.

In an article, “The Rape of the Appalachias,” published inThe Atlanticin 1962, he wrote of remote mountaineers in eastern Kentucky who were isolated from the industrial revolution and lived a life of hunting and trapping until after the Civil War. When outsiders started to come into the region, though, those locals were “putty in the hands of the Eastern capitalists,” he wrote (one imagines Daniel Boone meeting the Monopoly Man, who is cruelly twirling his mustache). The industrialists who came into the region in the beginning of the 20th century tore the trees off mountains, and then set to stripping the mountains of coal. The mines caused environmental problems such as flooding and pollution, which local counties had to pay to repair, Caudill wrote. After the companies were finished with the mines, they often didn't have to pay taxes on the land, depriving the local counties of tax revenues.

“The truth is that cheap power is being bought at a tremendous hidden and deferred cost which another generation will pay with compound interest,” he wrote, in the article.

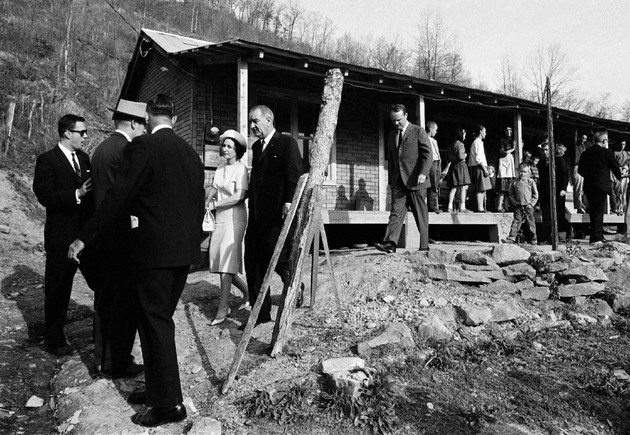

Caudill’s pieces and the book that followed,Night Comes to the Cumberlands,werelargely responsiblefor drawing national attention to Appalachia; when President Johnson visited Kentucky in 1964 to launch the War on Poverty, he made a stop in Inez, 80 miles of rough road north of Whitesburg.

President Johnson visited Inez, Kentucky, in 1964 to launch the War on Poverty. (AP)

President Johnson visited Inez, Kentucky, in 1964 to launch the War on Poverty. (AP)

But the subsequent years of federal dollars made little difference in the region’s poverty, and for decades, most locals stood by coal. Coal jobs allowed people with little else to make a good living, and the coal industry operates in boom and bust cycles, so even in slow years, they had no reason to believe coal couldn’t come back once again. Even today, Senator Mitch McConnell is still hell-bent onblocking regulationsrequiring states to reduce their dependence on coal-fired power plants.

But the region's dedication to coal may be changing. In 2013, Kentucky’s Governor Steve Beshear, a Democrat, and Congressman Hal Rogers, a Republican, convened a summit they called SOAR, orShaping Our Appalachian Region, in which local leaders came to the town of Pikeville to talk about opportunities beyond coal. For decades, any acknowledgement that coal might be on its way out of Appalachia was a third rail in Kentucky politics. But the SOAR summit, and talking about a world beyond coal, some local leaders say, really got people thinking about the future of the region.

“If it doesn’t accomplish anything else, what the Governor and Congressman Rogers did, they created a safe platform for leaders across Appalachia to talk about a new economy, a post-coal economy,” said James Hurley, the president of the University of Pikeville, one of the biggest colleges in eastern Kentucky.

The SOAR Summit coincided with federal investments in eastern Kentucky: The USDA spent $400 million in loans and grants to expand utilities such as wastewater infrastructure and broadband in the region. A national $5.2 million emergency grant has helped pay for a program called Hiring Our Miners Everyday, or HOME, that retrains miners or helps them find jobs outside the region. The Eastern Kentucky Concentrated Employment Program, a workforce-investment board focusing on the eastern part of the state, has received grants to retrain miners and other workers in growing fields such as healthcare, computer coding, and customer service.

A home near Whitesburg (Alana Semuels)

A home near Whitesburg (Alana Semuels)

A business launched by the investment board, USA Teleworks, trains locals to be customer-service representatives. It then matches them with companies from all across the country that are looking for reps who work from home. USA Teleworks is now expanding to hire and train workers from other states.

People who came from $70,000 a year mining jobs are often hesitant to take lower-paying, customer-service jobs, but the rapid decline of coal jobs has motivated people to realize they need to change their mindset, said Jeff Whitehead. There are 10,000 fewer people working in eastern Kentucky counties than there were a year ago.

But there are more opportunities for them than ever before. Some of those opportunities are home grown.

“It’s happening because of the crisis at hand,” he said. “People are really coming together and saying let’s make sure we’re going to develop a consensus as to where we’re going to go.”

* * *

People in the region are still looking for what is going to replace coal and government funding. That doesn’t mean a car factory or a different type of mining: Few people here want to see coal replaced by another extractive economy, allowing outsiders to get wealthy off the sweat of local workers.

Many of the people returning to the region say that any lasting, successful economic program is going to have to be home grown.

“How do we move forward as a region? The way that we do that is from within the region,” says Ethan Hamblin, who, at 23, is one of the many young residents who has made a commitment to staying in the area. “It’s not seeking outside funding, it’s getting the people on the ground working together across county lines, across state lines, and thinking about how we do that work together.”

Ethan Hamblin in downtown Berea, Kentucky (Alana Semuels)

Ethan Hamblin in downtown Berea, Kentucky (Alana Semuels)

While in college in eastern Kentucky, Hamblin began working for an organization that sought to foster a culture of philanthropy in Appalachia. If people with little to give started volunteering their time and donating what money they could to the region, they could help it become self-sufficient.

He was surprised how much people gave—whether it was signing up to run in a local race to benefit community nonprofits, or volunteering to teach farming to other locals.

The War on Poverty “was a complete flub, it didn't work,” he said. “There's a systemic culture of dependency, and that is deeply rooted.”

To shake it, he says, residents need to create their own economies, growing and selling food on land in eastern Kentucky, giving what money they can to others, volunteering at the local hospital or with people less fortunate.

“It’s about—how do we create those local internal systems instead of being dependent on large outside entities,” he told me.

The resources already exist in Appalachia to support that local ecosystem. While there is a lot of poverty in eastern Kentucky, there are still many people who have money to spend and time to give, said Peter Hille, the president of the Mountain Association for Community Economic Development, or MACED.

“It’s a common misperception about a poor region that everyone’s poor, but that’s not true,” he said.

The Treehouse Cafe, a gathering place started by an entrepreneur in Hazard, Kentucky (Alana Semuels)

The Treehouse Cafe, a gathering place started by an entrepreneur in Hazard, Kentucky (Alana Semuels)

One studyfound that $707 billion will be transferred between generations in Kentucky in the next 50 years. Groups like the one Hamblin represents are advocating for people to endow 5 percent of their wealth to the community in which they lived and made their money—including those who lived for awhile in eastern Kentucky and left. The state passed a bill in 2010 that incentivizes charitable giving by offering a 20 percent tax credit on endowments up to $50,000 made to a community foundation.

MACED has helped loan money to local residents to start businesses that cater to other locals, and also to people outside of eastern Kentucky. One former coal miner bought sheep from Vermont and created a business,Good Shepherd Cheese; another couple started at-shirt companywith funding from MACED, one woman started amobile dog-groomingcompany.

These businesses were founded with the idea that one big industry isn’t going to come in and save the region. But many small businesses can help jump-start economic growth.

“There’s not a silver bullet,” Hille told me. “There’s just a lot of silver beebees.”

A strategy of small-scale growth depends on people who commit to staying in Appalachia and growing their own resources. That’s where people like Ethan Hamblin and Ada Smith and Ivy Breasher come in. All grew up in eastern Kentucky, in a culture that by and large discouraged them to leave. And all three have come back, and are encouraging others to do so.

Whitesburg's town center (Alana Semuels)

Whitesburg's town center (Alana Semuels)

At a conference for Appalachian Studies a few years back, Smith and a few other young people started discussing how no one was really encouraging them to come home, and how for many of them, coming home might feel like a failure. They decided to create a group called STAY, or Stay Together Appalachian Youth. STAY, which includes people from Kentucky, Tennessee, West Virginia, and Virginia, is part social network, part professional-skills group, in which young, mostly college-educated people from Appalachia meet and talk about ways to better the local community. Their topics are as diverse as supporting local food systems and nurturing the LGBTQ community in Appalachia. It’s helped young people in the region meet others who are committed to living in Appalachia, and making it a better place.

The group was founded in 2008, but Smith, who works at Appalshop, says the idea of staying in the region seems to really be gaining traction now—perhaps because others in eastern Kentucky are also starting to think about a life beyond coal.

“The last two years have felt really, really different,” she said. “I feel like people are having conversations and willing to try different things that they never would have before.”

That feeling of optimism has spread to young people who aren’t involved in STAY, and who came to Whitesburg organically, because it seemed like a good place to live. I met some of them at Summit City Lounge, the nerve center of Whitesburg, which serves food and coffee during the day, and turns into a performance venue and bar at night.

The Summit Cafe on a Friday night (Alana Semuels)

The Summit Cafe on a Friday night (Alana Semuels)

When I showed up at 9 p.m. on a rainy and cold Friday night, the bar was mostly empty, and I figured I’d missed the night life, and that 9 p.m. was late for a rural area where dark and winding roads can make for dangerous commutes. But people slowly started to show up, and by 10:30, the bar was packed. A band played later in the night.

"A lot of us who are younger but didn't want to leave realized that if you want to do something, sometimes you have to actually make it happen yourself," Kevin Howard, who teaches traditional music in local schools, told me, standing outside the bar with friends. "You can't be dependent on someone else to employ you."

Howard has lived in Louisville and Atlanta, but keeps coming back to Whitesburg—this time, he thinks, for good.

I also talked to Seth Collins, 33, who used to work for a mine until he got laid off in 2012. In 2013, his former employer pulled up stakes in eastern Kentucky. But Collins, who is from Letcher County, still wanted to stay, even after he got a job at a bank in Pikeville, which is an hour away. He lives in Whitesburg and commutes to the bigger city every day. He and his girlfriend Meredith Matney live in Whitesburg in part because they enjoy the hikes nearby, and want to spend more time with family. But they like that when they look outside, they don’t see a dying town.

“Here, when I look out the window, I see young people,” he said, over the voices of the crowd in the bar.

“It really is a great sense of community,” she said.

* * *

Whitesburg is ahead of the game when it comes to thinking about an economy beyond coal. Herb E. Smith is part of the reason why. Smith’s family came to eastern Kentucky 200 years ago, and subsisted on agriculture and hunting in the mountains until the coal companies started mining in 1912. Then, his family members started working in the mines.

When Smith graduated from high school in 1969, the coal industry was in a decline, one of the many in the boom and bust cycles. He says 150 out of the 180 kids in his graduated class left, heading to the Midwest to work in auto-manufacturing plants and other factories. He wasn’t sure what he was going to do—his father and grandfather had worked in the mines, but there weren’t many jobs at the time.

But then, he says, “a spaceship landed.” Through a program funded by the War on Poverty, the Office of Economic Opportunity had set up aCommunity Film Workshopin Whitesburg. Locals like Smith had access to all sorts of new-fangled film equipment, which no one in the area had ever seen before.

Herb E. Smith in Whitesburg (Alana Semuels)

Herb E. Smith in Whitesburg (Alana Semuels)

The cameras were supposed to be used forvocational education, which made no sense to Smith and his friends. So they decided to start making documentaries and movies about the region, its culture and its people, and create a nonprofit, Appalshop, that would allow them to do so.

Smith caught me up on the historyof Appalshop, which is still around, in one of the new cafes in Whitesburg.

“We said, okay, we have a role to play here,” Smith said. They went to New York and asked for money from the Ford Foundation and other philanthropists. Henry Ford’s business thrived because of the coal mined out of the mountains in Appalachia, Smith argued, and philanthropies based outside out Kentucky had a role to play in preserving the culture of Appalachia.

“It was about revitalization. It was about remaking the place in a way that's sustainable—and saying this is our land and the land of our people. We're going to be here through thick and thin,” he said. “We knew it was important to do it, and if we could do it, it would be the most revolutionary thing we could do.”

Appalshop had—and still has—its critics. Because some of its founders spoke out against the coal industry, locals label them as hippies responsible for the death of coal. For a long time, people living in Whitesburg felt that they had to choose between coal and Appalshop.

“I do not take lightly to having my career being put on the line because you think these mountains are pretty and you've never had to put in a hard days work to provide for a family,” one minerwrote, when criticizing Appalshop, on a forumfor locals.

Still, creative types like the ones who started Appalshop can have a big role to play in economic development, asRichard Florida has written.

Appalshop hosts music festivals and showcases local art. (Alana Semuels)

Appalshop hosts music festivals and showcases local art. (Alana Semuels)

And Appalshop did help bring artists to the region, creating an annual festival called Seedtime that promoted the cultural heritage of Appalachia. The group also bought a building in town, and, not knowing what to do with it, provided a place for the local kids—including Smith’s daughter Ada—to play punk music and to hang out.

Those underground punk shows in the 1980s and 1990s started attracting people from surrounding counties, and created a community of young people who weren’t spending their weekends bored or doing drugs. Instead, they saw eastern Kentucky as a place that could nurture culture and attract interesting people. Many of the kids who grew up coming to the underground punk scene in Whitesburg are the ones who are now returning to live here for good.

“A lot of those young people really saw what was possible in this small coalfield mountain town,” said Herb Smith’s daughter, Ada.

* * *

Of course, there are many skeptics—at the $50 motel I stayed at on the edge of town, I talked to two clerks who grew up in Whitesburg and were just waiting for the first chance to leave. The idea to return to eastern Kentucky is in some ways is a privilege, since it assumes that leaving or staying is an active decision that a person makes. For many people in the region, whether to stay or not depends on whether they can find a job in Appalachia or elsewhere that will allow them to earn a living. They don’t have the luxury of choosing where that will be.

Ivy Breasher, another STAY member, says the people who stay in eastern Kentucky can’t expect to make $70,000 a year like they did in the coal days. They can have jobs that are more meaningful, she said, a job that “feeds your soul,” she said. But a soul is a tough thing to feed if your stomach is rumbling from hunger at the same time.

Not every business started up in Whitesburg has succeeded. A locally owned convenience store and vintage shop opened and closed, as did a bakery.

The town is still divided about alcohol sales—some blame astabbing last yearon the presence of the bars.

The Railroad Street Mercantile opened and closed in Whitesburg. (Alana Semuels)

The Railroad Street Mercantile opened and closed in Whitesburg. (Alana Semuels)

And even the people behind some of the more successful businesses aren’t sure that they’ll be around for good. They include Jonathon Hootman, one of the four co-owners of the new record store. Hootman, who is from Ohio, moved to Whitesburg for work because he is a seasonal bat biologist (seriously), and he fell in love with a woman and decided to stay. In June, he and three friends opened the record store with the idea of creating a place for the community to gather. But they’re not trying to make money—even though the rent is dirt cheap, and all four owners have jobs outside the record store.

The store is doing well, but Hootman says he isn't sure he would want to raise a child in Whitesburg, in part because schools are underfunded because of the population loss. And the downtown area is growing, certainly, but opening a business there isn’t a sure way to make money.

“I still think we are looking for that critical mass to keep things going. It kind of ebbs and flows,” he told me, from the quiet of the record store, where guitars and tapes and records were arranged in neat rows. “You think we have really got a lot of momentum going and going in the right direction and then a business will close or something.”

When I mentioned all the new businesses in town and asked a waitress at the local coffee shop whether she was optimistic about her kids growing up here, she was skeptical.

“What, my kids are going to work in a tattoo shop?” she asked me.

Roundabout Music Company, the new record store in Whitesburg (Alana Semuels)

Roundabout Music Company, the new record store in Whitesburg (Alana Semuels)

But working in a tattoo shop—or any of the new businesses popping up in town—might be a very real career for some people, which wouldn't have been possible before.

Curtis Cress, 30, worked underground in the mines for seven years, until the volatility in the business made him want to get out to have a more stable career to help support his wife and four kids. Cress, who had always been interested in art, found an apprenticeship in John Haywood's tattoo parlor.

He lives 45 minutes away in Perry County, but the commute isn't a bad one for eastern Kentucky. Now, he's getting ready to get a license and start earning more money, and says he thinks he's found a career that suits him well. It wouldn't have been possible a decade ago.

Whitesburg "used to be this small, dried-up town with nothing going on," he said.

Haywood, the tattoo shop owner, isn't sure that Whitesburg has really turned the corner and become a thriving town again. He stillworries when local stores open and then close, and when coal miners come in and tell him they're leaving, or that they've lost their jobs.

But if he can be part of a new community that breathes life into a town that could have had a very different fate, he says, he'll know that his gamble worked out.

“Sometimes I wonder if being here was the right choice,” Haywood told me. “Then I tell myself that I hope that I'm a part of something, and that maybe one day this will be a great cultural mecca, and I'll be the old dude that was around when it wasn't.”